For investors and financial analysts, scrutinizing a company’s balance sheet is standard practice. Yet, hidden within the liabilities section is a figure that can reveal a great deal about a company’s long-term financial health: its pension obligation. Understanding the distinction between the Accumulated Benefit Obligation vs Projected Benefit Obligation is not just an academic exercise; it’s crucial for accurately assessing a firm’s true liabilities. While both metrics quantify a company’s promise to its employees, they paint vastly different pictures of that promise. This guide will dissect these two pivotal concepts, explore how they are calculated, and clarify their impact on financial reporting.

What Is Accumulated Benefit Obligation (ABO)?

The Accumulated Benefit Obligation (ABO) represents the present value of pension benefits owed to employees based on their service and compensation to date. Think of it as a snapshot in time. If a company were to freeze its pension plan today, the ABO is the amount it would theoretically owe its employees, calculated without factoring in any future salary increases.

Core Definition: A Snapshot Based on Current Salaries

ABO is a liquidation-based measure. It answers the question: “What is the liability for all pension benefits earned so far if we only consider current salary levels?” This makes it a more conservative and less speculative measure compared to its forward-looking counterpart. Key characteristics include:

- Based on Past and Current Data: It only considers the years of service an employee has already rendered and their current salary level.

- No Future Projections: It explicitly ignores potential future pay raises, promotions, or career progression.

- Discount Rate is Key: Like all present value calculations, ABO is highly sensitive to the discount rate used, which is typically based on high-quality corporate bond yields.

How ABO is Calculated: Key Assumptions

Calculating the ABO involves actuarial science, blending several key inputs to arrive at a present value figure. The core components are:

Formula Insight: While the full actuarial formula is complex, the concept revolves around estimating future benefit payments (based on current salaries and years worked) and then discounting them back to their present value.

Key Inputs:

- Employee Service History: The number of years each employee has worked for the company.

- Current Compensation Levels: The salary of each employee at the time of calculation.

- Pension Plan Formula: The specific terms of the pension plan (e.g., 1.5% of final salary for each year of service).

- Discount Rate: The interest rate used to convert future liabilities into a single current-day value. A lower discount rate results in a higher ABO, and vice versa.

- Mortality and Retirement Assumptions: Actuaries must estimate how long employees will live and when they are likely to retire.

Because it doesn’t account for salary growth, ABO provides a baseline, a floor for the company’s pension liability under a static scenario. For a deeper understanding of how liabilities are presented on financial statements, a comprehensive guide to balance sheet analysis is an invaluable resource.

What Is Projected Benefit Obligation (PBO)?

The Projected Benefit Obligation (PBO) takes a more realistic, forward-looking approach. It is the present value of pension benefits owed to employees based on their service to date but calculated using projected future salary levels. This is the most commonly used measure for assessing a company’s pension liability on an ongoing basis.

Core Definition: A Forward-Looking Measure

PBO answers a more practical question: “What is the liability for all pension benefits earned so far, assuming employees will continue to work for us and receive pay raises?” It is considered a more complete representation of a company’s pension commitment because most pension plans base their payouts on an employee’s final or average salary, which naturally includes future raises.

Why Future Salary Projections Matter

The inclusion of future salary growth is the single most important distinction between ABO and PBO. This projection is critical for several reasons:

- Reflects Reality: Employees expect to receive raises over their careers due to inflation, promotions, and productivity gains. PBO acknowledges this economic reality.

- Matches Pension Plan Terms: Most defined-benefit plans link the ultimate payout to the employee’s salary near retirement. Ignoring salary growth would severely understate the final obligation.

- Required by Accounting Standards: Both U.S. Generally Accepted Accounting Principles (GAAP) and International Financial Reporting Standards (IFRS) require companies to use PBO for reporting the funded status of their pension plans on the balance sheet.

The projection of future salaries introduces an element of subjectivity. Actuaries must make assumptions about inflation rates, company-specific promotion tracks, and overall economic conditions. For those interested in the security and management of such long-term funds, understanding the principles of fund safety provides a broader context for corporate financial stewardship.

ABO vs PBO: A Head-to-Head Comparison

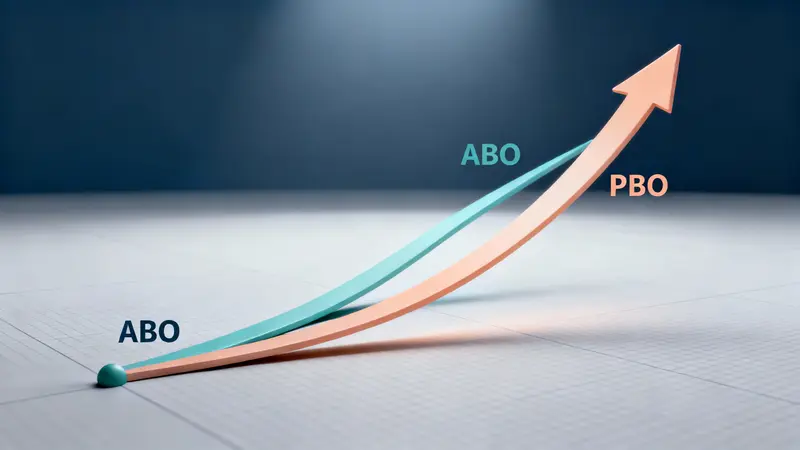

The core of the Accumulated Benefit Obligation vs Projected Benefit Obligation debate centers on one key variable: future compensation. This single difference has significant ripple effects on how a company’s pension liabilities are measured and reported.

The Primary Distinction: Salary Assumptions

To put it simply:

- ABO uses current salaries.

- PBO uses projected future salaries.

Because salaries generally increase over time, the PBO will almost always be higher than the ABO for a company with an active workforce. The gap between PBO and ABO represents the present value of the effect of future salary increases on pension benefits earned to date.

Impact on Pension Expense and Liability Reporting

The choice between ABO and PBO has direct consequences for the financial statements:

- Balance Sheet Liability: Under U.S. GAAP and IFRS, the number that appears on the balance sheet is the net funded status of the pension plan, calculated as Plan Assets minus PBO. A negative result (PBO > Assets) is reported as a net pension liability, while a positive result is a net pension asset.

- Pension Expense: The annual pension expense recorded on the income statement has several components, and the most significant one, the ‘service cost’, is based on the PBO. The service cost is the present value of benefits earned by employees in the current year, calculated using future salary projections.

Therefore, PBO is the more influential metric, directly impacting both the balance sheet and income statement and providing a truer picture of the ongoing cost of the pension plan. Reputable platforms like Ultima Markets often provide educational resources that help traders and investors understand these nuances in corporate financial reports.

A Simple Comparison Table: ABO vs PBO

| Feature | Accumulated Benefit Obligation (ABO) | Projected Benefit Obligation (PBO) |

|---|---|---|

| Core Concept | A snapshot measure, as if the plan were frozen today. | A forward-looking measure for an ongoing concern. |

| Salary Basis | Current salary levels only. | Projected future salary levels. |

| Key Use | Provides a minimum, conservative liability figure. | Used for financial reporting (balance sheet/income statement). |

| Typical Magnitude | Lower than PBO. | Higher than ABO. |

| Accounting Standard | Used for certain disclosures, but not for primary reporting. | Required by U.S. GAAP and IFRS for balance sheet reporting. |

Introducing Vested Benefit Obligation (VBO)

To complete the picture, there is a third, even more conservative measure: the Vested Benefit Obligation (VBO). This metric further refines the concept of pension liability by focusing only on the benefits that employees have an unconditional right to receive.

What is VBO and How Does It Fit In?

The Vested Benefit Obligation is the present value of pension benefits that employees are entitled to, even if they leave the company today. Vesting is the process by which an employee earns a non-forfeitable right to their pension benefits. For example, a company’s plan might require 5 years of service to become fully vested.

VBO is a subset of ABO. It is calculated using the same assumptions as ABO (i.e., current salaries) but only includes the portion of benefits for employees who have met the vesting requirements.

Comparing All Three: PBO vs ABO vs VBO

The relationship between these three obligations can be thought of as a set of nesting dolls, with each one encompassing the one before it:

PBO > ABO > VBO

- VBO is the most conservative measure, representing the absolute minimum liability for vested employees at current salaries.

- ABO builds on VBO by including benefits for non-vested employees, but still at current salaries.

- PBO is the most comprehensive measure, taking the ABO and adding the effect of future salary increases.

For investors, while PBO is the primary figure for analysis, a large gap between ABO and VBO might indicate a relatively new workforce that has not yet vested, while a large gap between PBO and ABO points to high expected salary growth.

Recommended Reading

To further your understanding of corporate financial health, explore our detailed guide on Cash Flow Analysis: A Complete Guide to Your Business. It provides essential tools for assessing a company’s liquidity beyond the balance sheet.

Conclusion

In the nuanced world of pension accounting, the Accumulated Benefit Obligation vs Projected Benefit Obligation comparison is fundamental. While ABO offers a conservative, liquidation-style view based on today’s data, PBO provides a more realistic and comprehensive measure of a company’s long-term pension promises by incorporating future salary growth. For analysts, investors, and finance professionals, PBO is the critical metric. It directly influences the pension liability reported on the balance sheet and the annual expense on the income statement, offering the clearest insight into the true financial commitment a company has made to its employees.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQ)

1. Why is PBO almost always higher than ABO?

PBO is nearly always higher than ABO because it incorporates a crucial assumption that ABO omits: future salary increases. Since employees’ salaries are expected to rise over time due to inflation, promotions, and performance, projecting these increases results in a larger calculated future benefit, and therefore a higher present obligation (PBO) compared to an obligation calculated using only current salaries (ABO). The only scenario where ABO might equal PBO is if a company’s pension plan benefits are not linked to salary levels (e.g., a flat dollar amount per year of service), which is very uncommon.

2. Which obligation measure is required by US GAAP for financial reporting?

For primary financial reporting on the balance sheet, U.S. Generally Accepted Accounting Principles (GAAP) requires companies to use the Projected Benefit Obligation (PBO). The funded status of the pension plan, which is the difference between the fair value of the plan’s assets and the PBO, must be recognized as either a net pension asset or a net pension liability. ABO and VBO are typically included in the detailed footnote disclosures of the financial statements, providing additional transparency.

3. What does an “underfunded” pension plan mean in relation to PBO?

An “underfunded” pension plan means that the company’s Projected Benefit Obligation (PBO) is greater than the fair value of the pension plan’s assets. In simple terms, the company’s long-term pension liability is larger than the investments it has set aside to meet that liability. This shortfall (PBO – Plan Assets) is reported as a net pension liability on the company’s balance sheet and can be a significant red flag for investors, indicating a potential future cash drain as the company must contribute more funds to cover the deficit.

4. How do changes in the discount rate affect PBO and ABO?

Both PBO and ABO are highly sensitive to changes in the discount rate, but in an inverse relationship. When the discount rate (typically based on high-quality corporate bond yields) decreases, the present value of future pension payments increases, causing both PBO and ABO to rise. Conversely, when interest rates and the corresponding discount rate increase, PBO and ABO will decrease. This volatility is a key risk that companies with large pension plans must manage.